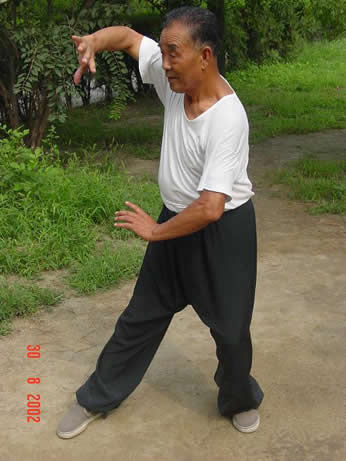

Han Fengrui

Tianjin, China - Gao style Baguazhang

(Base info written by George Wood)

One of my more memorable experiences studying martial arts was during the summer of 2002. I had the good fortune at that time to be able to spend some time with Han Fengrui in Tianjin, China. Han Fengrui was one of the top students of Liu Fengcai, a long-term student of Gao Yisheng.

One of my more memorable experiences studying martial arts was during the summer of 2002. I had the good fortune at that time to be able to spend some time with Han Fengrui in Tianjin, China. Han Fengrui was one of the top students of Liu Fengcai, a long-term student of Gao Yisheng.

I was able to meet Han Fengrui through a Gao Bagua cousin of mine named Hanan Magidovich, who was living in Tianjin and studying with Han Fengrui at the time (I say Bagua cousin not only due to our larger Gao style lineage - but also because Hanan had first come to the Gao style through our YiZong lineage - via Ziev Foux, a shixiong (elder brother) of mine under Luo Dexiu - Ziev is a tremendously powerful martial artist and a very honest and decent man (even if I only believed half the good stories Hanan told of him!)). I thank Hanan for introducing me to Han Fengrui so that I could learn some from him. Han had given up all public teaching at the time and it was only through Hanan that I was able to get time with him. You can read some of what Hanan has written about his training with Han Fengrui by following the links below and through the forum on this site.

Han Fengrui was in his mid seventies (74 - I believe) at the time of our meeting. He liked to claim that his skills went way downhill after he hit 60, but you could never tell the difference. He was very skilled in the art of Baguazhang and studied with Liu Fengcai for 20 years, from 1960 to 1981. He had also studied Xingyiquan and Wu style Taijiquan for decades as well.

Studying and meeting with him helped to confirm many different things in my study. Here was a man who had been practicing martial arts for the better part of six decades. He was still healthy, happy and practiced daily. As he had lived a long life, with his practice of Bagua central to it all, he had a very unique way of looking at training. He looked at things in the long-term. He said that up through one's twenties, one should practice for strength, stamina, and above all, fighting ability. One's thirties should be spent dedicated to the refinement of one's skill and power. From the forties onward, one should devote one's practice to the development of health.

My time spent learning from Han Fengrui was instructive as well. Although Liu Fengcai's style of Baguazhang has an obvious difference in the type of shenfa (body method) emphasized, what almost amazed me more was the similarities. One expects their to be "drift" in a style over generations, among practitioners, places and times. But, for example, when we compared our houtians - although there were some differences in the outer form, the applications and principles of each we found were remarkably similar. I was a little surprised, but pleased to see and experience the familiar.

He emphasized a much more closed and compact stance than what I had typically enjoyed practicing till then. The hips were tucked, the spine aligned vertically, chin tucked with feeling coming to the baihui point, legs were held close together and the arms were held more towards the center of the chest. He mentioned that movement of the body should come from the kua and that when the dantian qi is full, power will be able to come to anywhere on the body that it is needed.

As his personal practice had moved more towards tending to the health aspects of training, he would emphasize to me the health aspects of each of the xiantian circling changes. The snake form, for example, should emphasize one's arm aligned along the center of the body, helping to "extinguish heart fire" in this manner (you can see Han Fengrui's snake form smooth body palm in the second picture on this page - to the left). He would also emphasize heavily how one should breathe with the lower dantian. Moreover he would emphasize what I will call "breath control." He says that practice should be done such that one's breathing is under control the whole time - the baguazhang practitioner in his forms should not become out of breath or huff and puff - they should be able to control their breathing during the extent of their practice.

As his personal practice had moved more towards tending to the health aspects of training, he would emphasize to me the health aspects of each of the xiantian circling changes. The snake form, for example, should emphasize one's arm aligned along the center of the body, helping to "extinguish heart fire" in this manner (you can see Han Fengrui's snake form smooth body palm in the second picture on this page - to the left). He would also emphasize heavily how one should breathe with the lower dantian. Moreover he would emphasize what I will call "breath control." He says that practice should be done such that one's breathing is under control the whole time - the baguazhang practitioner in his forms should not become out of breath or huff and puff - they should be able to control their breathing during the extent of their practice.

He also related two stories to me about moderation in practice. One by telling of a Yin Fu stylist he had known by the name of Yu Chi. Yu Chi's student (or maybe it was this Yu Chi himself - my notes are unfortunately unclear) was one of the strongest, hardest working, and most powerful martial artists he had seen. He practiced nearly all the time in a very, very low posture (extreme low basin practice). Although this brought him great success in his youth, the man was apparently barely able to walk by the time he was 40 years old - and could never practice martial arts after that.

The second story was of himself when he was younger. His first martial art was Xingyiquan and he apparently took to its practice with zealous intensity. At one point he had been practicing an exercise that I assume was meant in part to train to take hard strikes. He was working with a larger classmate on a heng-ha exercise wherein your partner would strike you with a bengquan to the stomach while you emitted a "heng" sound and then strike to the chest with a straight piquan while you emitted a "ha" sound (or is it the other way around..?). Well, apparently Han's partner slipped up and ended up striking straight to Han's sternum, breaking some ribs in the process. Han gave up active Xingyi study after this for Baguazhang. My understanding of the morals to these stories were that moderation in practice is essential to life-long, balanced, healthy development in martial arts. It was apparent in his movements and in his attitude that he had taken those ideas as the law for his own practice.

The second story was of himself when he was younger. His first martial art was Xingyiquan and he apparently took to its practice with zealous intensity. At one point he had been practicing an exercise that I assume was meant in part to train to take hard strikes. He was working with a larger classmate on a heng-ha exercise wherein your partner would strike you with a bengquan to the stomach while you emitted a "heng" sound and then strike to the chest with a straight piquan while you emitted a "ha" sound (or is it the other way around..?). Well, apparently Han's partner slipped up and ended up striking straight to Han's sternum, breaking some ribs in the process. Han gave up active Xingyi study after this for Baguazhang. My understanding of the morals to these stories were that moderation in practice is essential to life-long, balanced, healthy development in martial arts. It was apparent in his movements and in his attitude that he had taken those ideas as the law for his own practice.

Although Han Laoshi personally emphasized health in his practice at this point (and he was quite advanced in age) he could still apply techniques with skill and power. He enjoyed working on different types of push-hands exercises as well as qinna (joint-locking) and counter qinna techniques. He had a remarkably strong grip for his age and would use his precise footwork to place himself in the proper position for an effortless technique. In fact I was also impressed by his footwork - he could move about quite well for his age, with speed and balance - and he relied on this footwork as the basis for much of his technique. In fact many of his push-hands types of exercises would emphasize the use of footwork, defensively and offensively.

Although I am sure Han Laoshi would shun and be embarrassed by any of this type of publicity, I would just like to again publicly thank him for the time he allowed me to glimpse a part of his art. It was wonderful to see how the practice of Baguazhang can bring health, skill and happiness throughout all of one's life.

You can find information, stories and more about Han Fengrui as written by his student Hanan Magidovich by clicking on the links below.

Introduction to Han Fengrui by Hanan Magidovich